Mind-mapping workshops

-

Synopsis

SYNOPSIS

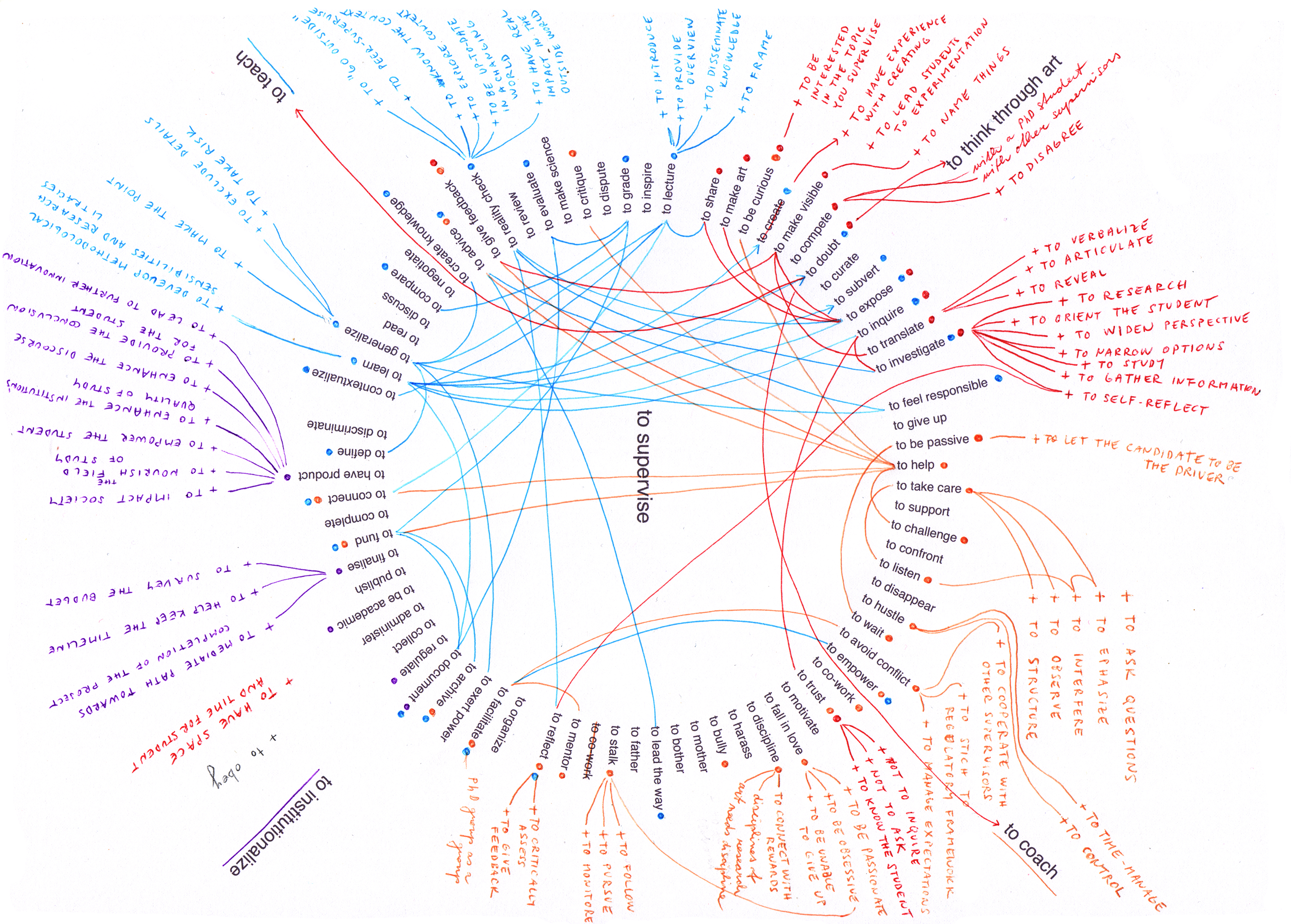

Over the course of our project time six brainstorming sessions and workshops have been realized in Bergen, Prague and Stuttgart. On these occasions we developed mind-mapping workshop strategy that can be easily used in new setting with the primary aim: to bring various actors in artistic supervision around the table. At any institution or across institutions, this pop-up workshop can create a specific, inter-related and situated archive of ideas, notions and tools collectively. It is always constructed anew.

We explored the boundaries of supervision, aiming to come up with a working definition of what notions supervision is connected in minds of supervisors, doctorate students and institutional actors. We advanced and situated the concept of doctoral supervising within larger clouds of practices around thinking through art, coaching, institutionalizing and teaching.

What other verbs come to mind when we say ´to supervise´ in the context of artistic research? The verbs inscribed in the inner ring represent the harvest of all verbs the project partners come up with in the first brainstorm session in Bergen. All these initial verbs are inscribed in the circle to form a dial around which participants sit around the table.

The four main tags are selected from the pool of initial verbs in the central ring as the main concepts that define supervision. Here we nominated following verbs: to teach, to coach, to institutionalize, to think through art. These are always decided collectively anew.

To construct a deeper mind-map we multiplied this basic frame in the form of large printed A0 table grid on canvas. It can be copied cheaply on used papers at art schools, drawn by hand, or directly reused online on a tablet. We used paper copies for 4 table-game workshops during The ELIA Academy, co-hosted by Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design, and State University of Music and the Performing Arts Stuttgart „The Boundaries, Challenges and Potentials of Doctoral Supervision in Relation to Mentoring, Coaching and Teaching in Artistic Research“.

Credits

We want to thank all project partners and participants in our workshop sessions and discussions „The Boundaries, Challenges and Potentials of Doctoral Supervision in Relation to Mentoring, Coaching and Teaching in Artistic Research“during the ELIA Academy, co-hosted by Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design, and State University of Music and the Performing Arts Stuttgart in September 2019. Their many insights informed this map and we will make sure we keep it alive and open for further academic re-use.

Project team of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague

Anna Daučíková, Maria Topolčanská, Tomáš Pospiszyl, Dušan Zahoranský in collaboration with Vít Havránek, Magda Stanová, Danica Dimitrijevic, Ondřej Buddeus.

Design

Jakub Mynář, Maria Topolčanská

-

The Making of (a manual)

The Making of (a manual)

Session 1 (50 min)

-

Ask the 5-10 participants to take one of the cards on the table. Each has one of the verbs inscribed on it. Ask them to consider the following:

What is the AGENCY of the verb on your card in the context of supervision based on your understanding? What it enables or prevents from in the process of supervision? - Note your idea directly to the canvas or on a separate paper.

- Engage in a group talk around the table. Ask participants to present shortly (5 min each) their verbs with brief definition of their agencies.

Break

Session 2 (50 min)

- Put only the cards used in previous session in the centre of the canvas.

- Ask participants to take any of the cards with verbs and to take 10 minutes to individually brainstorm first. Ask them to consider the following: What are the TOOLS we need related to the verb on your card in the context of supervision and the agency described earlier? Write your notes on tools on the canvas or on a separate paper.

- Discuss as a group around the table, the arguments will be recorded.

The results of these many encounters around the table are a post-produced drawing and this online mind map simultaneously.

The map is building on both the verbal and the visual.

It is based on selected arguments from the transcript of the situated and recorded discussions and on the drawings on all four table grids where new verbs, ideas, arguments and connection lines were introduced by all across the canvas.

The mind map is always to be enhanced.

It is to be open to grow anew.

-

Ask the 5-10 participants to take one of the cards on the table. Each has one of the verbs inscribed on it. Ask them to consider the following:

Workshop results

-

To institutionalize

TO INSTITUTIONALIZE

Vít Havránek

Moderator, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague

Frida Bjork

Ingvarsdottir Iceland University of the Arts, Iceland

Klaus Jung

Royal Academy of Art the Hague, Netherlands

Rui Marques Pinto

Integrations Council Reutlingen, Germany

Giaco Schiesser

Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), Switzerland

Olof Sigfusdottir

Iceland University of the Arts, Iceland

Henk Slager

HKU University of the Arts Utrecht, Netherlands

Bert Willems

MAD School of Arts, PXL University College, Belgium

Andrea Braidt

University of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

A good supervisor should be artistic, be an expert, think through art, good artist, have own practice.

But I wouldn't say that only written things are academic. – It's about being rigorous, being concise. – It's more about to be able to articulate: in order to be academic you have to articulate on whatever you're reflecting on and what you're doing.

But it's also maybe about this thing that is inherent in art studies that you don't think. Thinking through art is academic enough. It's a problem that we are facing sometimes that art practice is not seen as academic work. And I think we need to somehow overcome that. It was done in Iceland through legislation, which basically says, in the university law, that it is an academic work. And it helped a lot. It helped to bring the discourse to a different level. So we were not so worried about people not writing long dissertations and so forth. They just do their thinking and their projects in a different way, they mediate in a different way, and they have a different impact on society. So it's also a question how you think about research, what is interesting.

I'm an art historian, and when you mentioned to be academic, the first meaning for me was the type of artistic practice that is linked with the renessance and classical art—to work with pure drawing and certain ideas about drawing. All the academies of fine art are called academies because they relate to this renessance and antic meaning.

We are academies, so we have to be academic in our own way.

When we are thinking about concrete tools, selection is an important tool that can be developed. We should really put energy into selecting students which have potential. Not everybody has this potential.

There is a problem if an institution wants to have many doctoral students.

But if you go one step beyond the selection, it would be something like scouting, because only certain people with certain social culture capital would apply. So how to search for these people who would not apply, but would be exellent students, but they don't apply because of certain social conditions, etc. — That also applies to bachalor and master programs.

In Iceland, we are required by law to teach in Icelandic. We do teach master programs in English, but it's an exception, because the whole country is trying to preserve this endangered language, and it's a part of the state policy. There are ways around it, but it is also about enhancing the quality of life within your own community. That's what education is for. But it should be an obstacle when it comes to working internationally.

In Norway, it's also both. We recruit so many international professors, and you cannot expect them to learn Norwegian. Commitees are international as well.

To have a product: It's a very strange keyword.

It's very much approaching education through commodification of education.

It's so neoliberal.

For institutes, it makes sense if you define it as impact, if you want to be relevant..

This product-oriented aim in academia.. ranking...

It's interesting because in a lot of discussions about artistic research it's always about process.

So we are skeptical about "to have a product".

You are not supposed to think in terms of a product.

It could be to produce, to document, to finalize instead of to have a product.

A lot of American universities define on their webpages what the product of the studies is.

Universities are asked to have a PhD as a product.

It's a dirty word. (To have a product)

To regulate: How do you regulate how much time a supervisor is supposed to devote to doctoral students?

It should be clearly defined how many hours a year it should be. In Helsinky, it was 80 hours a year in order to supervise a candidate, some schools have 40 hours, some don't have defined it at all.

If it's not defined, it can happen that a professor have some favourite students and then they devote more time to them.

When it's defined, then a student knows and can say that I have 80 hours.

Many professors say that they have an overload of work, and, if they supervise too many doctoral students, they don't have time to do anything else. To it's a good way to keep working hours of professors regulated as well.

In our institute it is divided 50% for research (including supervising) and 50% for teaching.

To document: Many institutions have archival assistants.

At Oslo National Academy of Performing Arts, all performances are video-documented and archived. So you need to have the equipment and people who do the job. And, also, people who make it available on-line.

We also have to accept that we cannot document everything. There's a kind of a document fever. Nobody will access all these things. It's too much.

How can we better share internationally these processes?

I really believe in these conferences where artistic research is being presented. But research is traditionally building on somebody else's knowledge. In artistic research, the references are often there but difficult to find (much more difficult than in traditional research). And earlier research in this field is scarcely referred to. And that is really a challenge for us.

What would be the better tool to navigate through already existing research?

As of now, it's almost a hear-say. "I heard that...", "You said...", "Did you see...". It's not based on actual references.

We should regulate the amount of quotations. (laughter)

We still talk about supervising from an ego perspective. And, basically, we could also introduce the notion of collective agency and do it with more people all together. Otherwise only one person is responsible. Of course, it's also a matter of money and organizing.

I don't know much about what is going on in the other art universities in Europe except from what I see exposed at conferences. There might be a lot of good research going on. But at these artistic research conferences we are rarely exposed to the research that is going on within the institutions by academics and professional [researchers?] than the PhD candidates. Research within institutions is very seldom. We are missing out a lot.

What is also interesting to observe is that these artworks that are results of doctorates are slightly different from regular art production. There is some kind of complexity that is created by academies, by institutions, and this complexity is difficult to communicate or disseminate through regular art channels (museums, galleries, curators). So this is a contradiction that appears, and it produces some kind of academical type of aesthetics or art.

I think it would be good if institutes communicated about their narratives. I don't believe in centralizing, in building up a platform for building up one narrative. I think it has to be build within these institutes, and then they need to take care of it, and communicate about their narrative.

-

To coach

TO COACH

Tomáš Poszpisyl

Moderator, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague

Beate Boeckem

Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), Switzerland

Manuel Damasio

Universidade Lusófona, Department of Cinema and Media Arts, Portugal

Florian Dombois

Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), Switzerland

Robert Burstow

University of Derby, School of Arts, United Kingdom

Wiesel Jorg

FHNW Academy of Art and Design, Switzerland

Victoria Preston

Research Platform and Doctoral Practice in Arts (RPDP-A), United Kingdom

Ghellal Sabiha

Hochschule der Medien, Stuttgart, Germany

Michaela Glanz

Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

To be passive: to trust, to wait, to listen

But when you listen, you need to be active.

You can listen attentively.

To try to empower.

To detach, to not engage.

To help: to be informed, to critique, to advice, to fund, to connect

We have this attitude, especially in art schools, that we always want to help students in any respect on all levels—bachelor, master, PhD. But I wonder if that is the only attitude that you should have. Could it be also to challenge? Sometimes I'm missing that aspect in art schools that we challenge each other. Because it's a form of patronizing when you always say "How can I help you?".

To dispute: I always ask people why they're doing it. Because they have often forgotten their internal[?] motivation, so I'm making them write down continually why they are doing it. And it doesn't matter if the reasons have changed, but there needs to be a reason all the time, a conscious reason for their research whether it's in terms of academic or personal professional. I try them to separate what you're contributing to academic knowledge and what you're contributing to yourself personally, maybe in terms of self-esteem. Will it help you professionally or is it just something you're really interested in. It doesn't matter what the answer is as long as there's clarity in the student's mind. So I think, as supervisor, to ask questions is really important until students figure out the answers that are relevant for them.

I like that to mother and to father are so close to each other.

I think it sometimes helps to co-work, because it takes away this mentor thing—we are equal and we're researching together.

For example, one person does game art and the other one game design. Or, in a theatre production, one is doing stage design and the other directing.

This is normal in science that a supervisor publishes together with students.

We have one professor that demands from students to co-work: to find or to create a situation for collaborative projects, or to fail trying to work together. And these are not necessarily interdisciplinary projects where you need an expert. It's just to try the situation where you're not the only creator but you have to collaborate with others.

The German and Austrian art schools have this tradition of hiring a professor and giving him a studio. And then the students work with him in the studio. In Switzerland professors are hired for teaching, so you come in for the hour you teach, and then you go away. It's the the opposite direction, as a counter-agent. But what it produces is that there is no professional level of the art production in the art schools any more, because everybody is leaving. And I wonder how cooperation and co-working spaces can be created and not to fall back to old-fashioned past.

That's a very dangerous frontier, but then sometimes what happends is that a supervisor is taking the students to their own professional environment, and that creates a lot of ethical complaints.

To mentor: space (more than a shared table)

I like the word empathy better than to take care, because to take care dispowers the other person, because you're telling them what to do. To empathise means that you empathy for the situation—where they are, what they need, and when they need it.

Is mentoring different on the PhD level?

From my experience, there is not enough distinction between these MA studies and PhD studies on art schools. PhD studies are almost a continuation of master studies. A PhD student must be someone who works truly independently, has to have an ability to reflect on a high level what they're doing. This doesn't necessarily mean that they have to be art theorist, but it's a different approach than usual artistic careers.

I'm finding it very difficult to [make them] write in their own voice, which is so important, and to write clearly, but also to write in an analytical, critical manner, not descriptive. So I'm torned[?] between chunks of description and chunks of material that is too closely related to the source texts. And a difficulty to construct an argument which is integrating and flowing.

Already from bachelor and master studies we know that a lot of visual artists have troubles to write a thesis. And I think it's partly because writing is a difficult practice (PhD dissertation was my first thing to write ever—to write 200 pages that was a nightmare), but partly also because of this non-poetic way of writing in academia that is bullying me as an artist. I feel visibly bullied by some form of text, when I'm totally delleuzed by everything.

I'm not talking about academic writing; I'm talking about clear practical writing which is different. We are not aiming for obscured deleuzian-laconian academic style, we are looking for criticality, clarity, coherence.. I say to the students "try to write as you speak", because often we speak more clearly than we write, and always then refine it and add references. And my other idea, which is more of an artistic idea, is to think about writing as about sculpture—I have words, which are like clay, and I try to mould these words into something beautiful and coherent and good to read. Maybe that's something that artists can relate to. Writing has physicality, it's not just thing in the brain.

I remember when, at the beginning of me writing, I realized how can I live in that verbal space, like I can be in the studio, and that there are certain words that can be strong and hard, or cold, and I can mould them, etc.

Most artworks that are really of interest are highly reflective. I mean on the level of reflexivity that academia is missing, I would even say. Why don't we dare to take a stand and say "obviously, this is a self-reflective work".

You have three experts that are well-known and they are looking at the video and read the text, and they judge it in the exactly the same way as scientists would read dissertations and ask critical questions.

In order to be a good mentor, you should get rid of marks.

Do you know the book of David Hockney titled The Secret Knowledge? I think that's a wonderful example of how to contribute to the field. Especially because art historians really hated it, because it's partly not true in a logical sense. — I'm an art historian, so I can say that, yes. But on the other hand, he sort of [?] that you do not need to know in order to tell something. He has played the role of ignorant school master[?] and taught us, art historians, something new[?].— You can look at the book on two levels: One is towards art historians, and it's funny how he has quotes where he says that that's an invented quote by ... so, you know, he is playing that game. But, reading it as an artist, I really don't care whether they used these mirrors or not. I think he is training me to look on old paintings in a different way, because this play of perspective is indeed in some images extremely present and in others not. It's a way of looking at this huge wall that he is talking about; it's a way of reading painting. And he has a way of sharing that through this story. And I like it.

I had a big fight/discussion, because we are talking about categories or principles, when we started the review process at JAR. He always wanted to have guidelines for the reviewers, and I refused. And then he found a very smart solution: he wrote a list of what is research (reflexivity or whatever), and the last one is always "or non of the above and why not". And I really like that—there's always an opening. Maybe our categories are wrong.. So I would always drill such holes to the form of boxing.

As an ELIA group, it would be good to have an overview of what are the important platforms to disseminate art research. I think if would really help to know which are the genres, which are the conferences, application possibilities that would be suitable, because that's what PhD students ask me very often. To which conferences should I go...

I always encourage the students to quote other PhDs.

I think it would be really helpful not only to map what exists, but also to have a place to discuss on new forms of artistic PhDs. That would be a group that I would really like to join.

I've seen so many PhDs, and I'm rarely really excited.

For a while, [they used to tell us that the] only reason why we are talking about artistic research is the change from art schools to polytechnics and from polytechnics to universities, and universities are funded through research, and all of the sudden art schools are forced to do this. I remember 25 years ago, the UK colleagues asking us "Why do you engage with research without any need for it." But, I think something [?] is happening. I think we all start to discover a [?] in that research.

It's a chance for the art world to have an area where it's advancing its own qualities.

In the national science funding council in Spain, we are in the same category with humanities. That creates a lot of troubles. I don't see any reason for that. — I always wanted to move to engineering, because they also need labs and facilities.

-

To teach

TO TEACH

Maria Topolčanská

Moderator, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague

Judith Schwanke

Zurich University of the Arts (Zhdk), Switzerland

Claus Peder

Pedersen Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark

Fabiana Senkpiel

Bern University of the Arts, Switzerland

Susan Halvey

Limerick School of Art and Design, Ireland

Lucia Hornakova

University of Economics, Prague, Czech Republic

Veerle Van der Sluys

LUCA School of Arts, Belgium

Hana Pruchova

Janacek Academy of Music and Performing Arts, Czech Republic

To check reality means that students should have access to knowledge—it means, for example, that our library offers licences to various scientific websites where they can find some important resources. Supervisors need it as much as students. Supervisors need access to knowledge. It is very connected to learning: if you want to lead a student to be up-to-date, also you, as a supervisor, need to be up-to-date, to actualise yourself, to learn, to get knowledge.

I'm thinking of a dedicated studio for PhD supervision (rather than a seminar context with a screen, PowerPoint, and people sitting in chairs) that could be booked for the supervision. So that supervisors come to a space, where a student sets up and puts the work in. It's a way that is more sympathetic, so that the student is not going to an office, but they are going to a space where there can be more collaborative supervision.

The canon of methodological literacy is still evolving within the arts. In the hard sciences and social sciences you have theories on checking credibility or trustworthiness or validity in research. But do we have a similar smorgasboard of reliability, that's probably the wrong term, but trustworthiness or credibility for assessing artistic research.

It's true, because mostly we answer that a tool is kind of every occasion on which a board, or a jury, or a collective of some evaluators or assessors, supervisors, meet and interact with this, but these are often individuals who also can have methodological illiteracy in this, to be self-critical. So this is a question that sometimes we have a tool, which is jury-like or more informal, peer-like, set of people who try to make this happen, but where do we have this methodological self-assurance?

So, for example, if a student is close to burnout, what should you do as a supervisor?

As an educator, you are responsible in some way for an emotional well-being of the student.

We have a faculty psychologist.

I think this is where teaching and supervising differs very much: how very strictly clear is the time spent, and what's happening in the agency of "to teach"; and how "to supervise" is much more heterogeneous unexpectable.

A collaborative supervision is happening in practice, but it's such a socially uneasy situation—what is prescribed and what is optional, how this collectivity of supervisors is given or chosen by the PhD student.

-

To think through art

TO THINK THROUGH ART

Magda Stanová

Moderator, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague

Raivo Kelomees

Estonian Academy of Arts, Estonia

Lukas Rieger

Janacek Academy of Music and Performing Arts, Czech Republic

Cecilie Broch Knudsen

The Norwegian Artistic Research Programme, Norway

Zuzana Buchova Holickova

Academy of Performing Arts Bratislava (VSMU), Slovakia

Elisa Campanella

Independent, Italy

Andrus Ers Konstfack

University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, Sweden

David Huycke

MAD School of Arts, PXL University College, Belgium

Sophie Schober

Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

We have programs, where a lot our supervisors don't have a PhD. So they never studied a PhD, they never were in this position, and now they have to lead PhD students.

From the point of view of an institution, the PhD student is a product, to say it in a cynical way.

Now the PhD students are also very creative in how to verbalize their research thoughts. And I think we also need to give them space to develop new methodologies of [?]. We need to be creative and trustworthy towards the students.

In art, artist are usually like "it's mine". In artistic research, others should be able to build on the top of it. So these are two conditions—extending knowledge/understanding and others should be able to build upon it. And it's easy, when something is verbalized, to build upon it and to understand what view was brought, but maybe these two conditions could be fulfilled also when the form is other than text. Artistic practice is, in a way, similar to that of engineers. They make a prototype of something. And maybe it's also explained in a text, but the prototype itself is also very important for understanding.

We have an example of this in our school where a graphical designer, in his PhD, designed a book that contains the history of fonts, and he proposed it as a final theses book. But then, he was forced to write an additional text to explain it, to mediate it. [?] We were not brave enough to experiment.

To be curious: the ability to ask questions how and why. To be really interested in the topic of the candidate you're supervising.

If you're not interested in the topic of the candidate, then you can't be a supervisor. Then it's like being a manager: you look if all the administration is done, look at some methodology, and then ok.

To compete: It happens between supervisors as well. When there are two or more supervisors, it's some sort of dialogue, but it could be an antagonistic dialogue as well.